Chapter 1: Sideshow

The Thunderbolt rollercoaster, a few weeks before its surprise demolition by the city in 1999. Coney Island USA artistic director Dick Zigun speculated, “It seems that some people think of the Thunderbolt as an urban blight eyesore that needs to come down before the minor league baseball stadium opens in June.”

The Thunderbolt rollercoaster, a few weeks before its surprise demolition by the city in 1999. Coney Island USA artistic director Dick Zigun speculated, “It seems that some people think of the Thunderbolt as an urban blight eyesore that needs to come down before the minor league baseball stadium opens in June.” One of Thor Equities' renderings of its vision for a future Coney Island, complete with giant yellow elephant, reimagined parachute jump, and Batman.

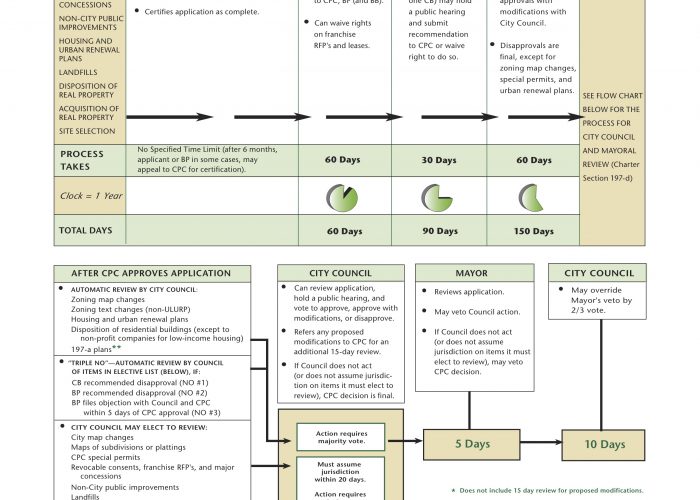

One of Thor Equities' renderings of its vision for a future Coney Island, complete with giant yellow elephant, reimagined parachute jump, and Batman. The city's Uniform Land Use Review Process, or ULURP: a simple diagram.

The city's Uniform Land Use Review Process, or ULURP: a simple diagram. Coney Island's annual trash-can-painting contest generated some political statements from opponents of the planned redevelopment.

Coney Island's annual trash-can-painting contest generated some political statements from opponents of the planned redevelopment. The Coney Island Development Corporation's vision for the amusement district earned its own points for grandiosity.

The Coney Island Development Corporation's vision for the amusement district earned its own points for grandiosity. City councilmember Domenic Recchia speaking at Astroland's first "final day" in September 2007. Recchia, an old friend of Thor Equities developer Joe Sitt, would later force the city council to back down on plans to ban highrises between Surf Avenue and the boardwalk.

City councilmember Domenic Recchia speaking at Astroland's first "final day" in September 2007. Recchia, an old friend of Thor Equities developer Joe Sitt, would later force the city council to back down on plans to ban highrises between Surf Avenue and the boardwalk. Coney Island USA founder Dick Zigun outside the Astroland gates, September 2007. “It’s both the genius and the bane of Coney Island is that it’s not centrally managed," he had remarked earlier. "And small-time idiots get to try out new ideas here — most of which is horrible, some of which are brilliant.”

Coney Island USA founder Dick Zigun outside the Astroland gates, September 2007. “It’s both the genius and the bane of Coney Island is that it’s not centrally managed," he had remarked earlier. "And small-time idiots get to try out new ideas here — most of which is horrible, some of which are brilliant.” A band plays Astroland out into the night, September 2007.

A band plays Astroland out into the night, September 2007. Astroland closes for good this time following Joe Sitt's refusal to grant a lease extension, September 2008.

Astroland closes for good this time following Joe Sitt's refusal to grant a lease extension, September 2008. The Scrambler takes a final spin, Astroland, September 2008.

The Scrambler takes a final spin, Astroland, September 2008. Last night at Astroland, September 2008. Just after 11 pm, owner Carol Hill Albert got on the PA: “Astroland guests, please begin moving toward Surf Avenue. We are closing the park. Thank you very much for coming, and we’re sorry we have to start closing now.”

Last night at Astroland, September 2008. Just after 11 pm, owner Carol Hill Albert got on the PA: “Astroland guests, please begin moving toward Surf Avenue. We are closing the park. Thank you very much for coming, and we’re sorry we have to start closing now.” Astroland three months after its final closing in 2008.

Astroland three months after its final closing in 2008. The Astroland teacup ride is packed up in preparation for sale and relocation.

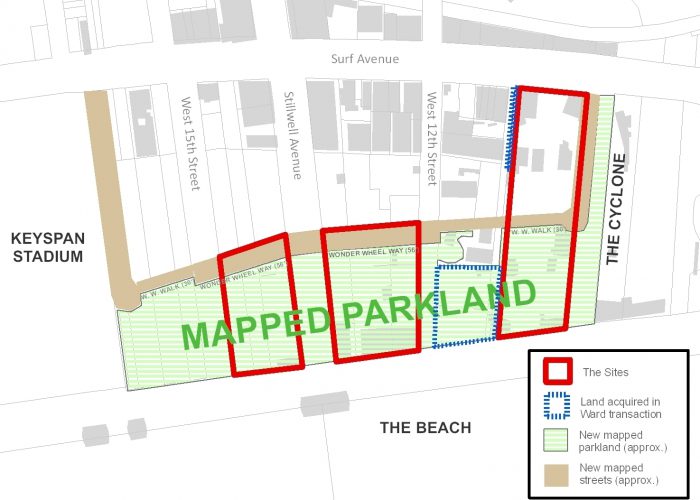

The Astroland teacup ride is packed up in preparation for sale and relocation. The city's scaled-back amusement district plans (in green) and the 6.9 acres of properties it paid Thor Equities $95 million to obtain, double what the developer had paid for it prior to the rezoning plans.

The city's scaled-back amusement district plans (in green) and the 6.9 acres of properties it paid Thor Equities $95 million to obtain, double what the developer had paid for it prior to the rezoning plans. In October 2012, Hurricane Sandy toppled trees throughout the beachfront, especially in Coney Island's Asser Levy Park.

In October 2012, Hurricane Sandy toppled trees throughout the beachfront, especially in Coney Island's Asser Levy Park. The Eldorado bumper car concession on Surf Avenue, after being inundated by Hurricane Sandy's storm surge.

The Eldorado bumper car concession on Surf Avenue, after being inundated by Hurricane Sandy's storm surge. In Coney Island's residential West End, a bus shelter shows the high-water mark during Hurricane Sandy.

In Coney Island's residential West End, a bus shelter shows the high-water mark during Hurricane Sandy. Following Hurricane Sandy, Mermaid Avenue became a sea of trash bags as store owners cleared out debris and sodden merchandise. "We can’t shop, there’s no stores out here," said local resident Joyce Grace. "Where am I supposed to go buy food?”

Following Hurricane Sandy, Mermaid Avenue became a sea of trash bags as store owners cleared out debris and sodden merchandise. "We can’t shop, there’s no stores out here," said local resident Joyce Grace. "Where am I supposed to go buy food?” Mermaid Avenue store owner Yousef Alhamshali shows the height of the storm surge inside his corner grocery. “We lost everything, simple and easy,” he said.

Mermaid Avenue store owner Yousef Alhamshali shows the height of the storm surge inside his corner grocery. “We lost everything, simple and easy,” he said. Inside Victoria Hammond’s basement apartment on West 37th Street, her refrigerator sits in the middle of the floor, moved there by an 11-foot wall of water during Hurricane Sandy. “This used to be a whole apartment,” she said. “I lost everything.”

Inside Victoria Hammond’s basement apartment on West 37th Street, her refrigerator sits in the middle of the floor, moved there by an 11-foot wall of water during Hurricane Sandy. “This used to be a whole apartment,” she said. “I lost everything.” Relief efforts came late to Coney Island's West End, much of it provided by local church groups and grassroots organizers. “No one was out there saying, ‘Look at the Cyclone, it’s sheared in half,’” noted Occupy Sandy organizer Eric Moed of the lesser damage to the amusement district. “Then once you start canvassing the buildings and seeing the residents, it’s deplorable.”

Relief efforts came late to Coney Island's West End, much of it provided by local church groups and grassroots organizers. “No one was out there saying, ‘Look at the Cyclone, it’s sheared in half,’” noted Occupy Sandy organizer Eric Moed of the lesser damage to the amusement district. “Then once you start canvassing the buildings and seeing the residents, it’s deplorable.” On the second floor of a Housing Authority building in Coney Island's West End, seawater still stands on a second-floor hallway a week after Hurricane Sandy. Years later, as repairs still lagged, tenant leader Steve St. Bernard remarked: "Once you hit 23rd Street, where everything is still messed up? We call it the dark side.”

On the second floor of a Housing Authority building in Coney Island's West End, seawater still stands on a second-floor hallway a week after Hurricane Sandy. Years later, as repairs still lagged, tenant leader Steve St. Bernard remarked: "Once you hit 23rd Street, where everything is still messed up? We call it the dark side.”

Buy "The Brooklyn Wars" paperback

Buy "The Brooklyn Wars" ebook